After a long festival run, Blackfish is finally hitting general theaters. There is a premiere in LA tonight, and then it rolls out in selected theaters across the country.

Here’s the current schedule:

play dates

|

|

After a long festival run, Blackfish is finally hitting general theaters. There is a premiere in LA tonight, and then it rolls out in selected theaters across the country.

Here’s the current schedule:

|

|

If you aren’t familiar with the amazing and touching story of Luna, the whale that reached out to humanity, The Lost Whale, from Michael Parfit and Suzanne Chisolm, is a must-read.

If you aren’t familiar with the amazing and touching story of Luna, the whale that reached out to humanity, The Lost Whale, from Michael Parfit and Suzanne Chisolm, is a must-read.

And even if you are familiar with the story–which was featured in Parfitt and Chisolm’s documentary The Whale, you’ll learn lots more.

Here’s the book description:

The heartbreaking and true story of a lonely orca named Luna who befriended humans in Nootka Sound, off the coast of Vancouver Island by Michael Parfit and Suzanne Chisholm.

One summer in Nootka Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, a young killer whale called Luna got separated from his pod. Like humans, orcas are highly social and depend on their families, but Luna found himself desperately alone. So he tried to make contact with people. He begged for attention at boats and docks. He looked soulfully into people’s eyes. He wanted to have his tongue rubbed. When someone whistled at him, he squeaked and whistled back. People fell in love with him, but the government decided that being friendly with Luna was bad for him, and tried to keep him away from humans. Policemen arrested people for rubbing Luna’s nose. Fines were levied. Undaunted, Luna refused to give up his search for connection and people went out to meet him, like smugglers carrying friendship through the dark. But does friendship work between species? People who loved Luna couldn’t agree on how to help him. Conflict came to Nootka Sound. The government built a huge net. The First Nations’ members brought out their canoes. Nothing went as planned, and the ensuing events caught everyone by surprise and challenged the very nature of that special and mysterious bond we humans call friendship. The Lost Whale celebrates the life of a smart, friendly, determined, transcendent being from the sea who appeared among us like a promise out of the blue: that the greatest secrets in life are still to be discovered.

You can order The Lost Whale here.

Fresh from the kickass movie-trailer production facility. Check it:

The poster for the general theater release on July 19 is out. Looks good, no?

If you want to know how the whole raking-in-the-bucks-by-putting-killer-whales-on-public-display thing really got rolling, you need to know the sad and enraging story of Moby Doll.

Recently, there was a gathering to reflect on the (almost) 50-year anniversary of Moby Doll’s capture, and all that followed:

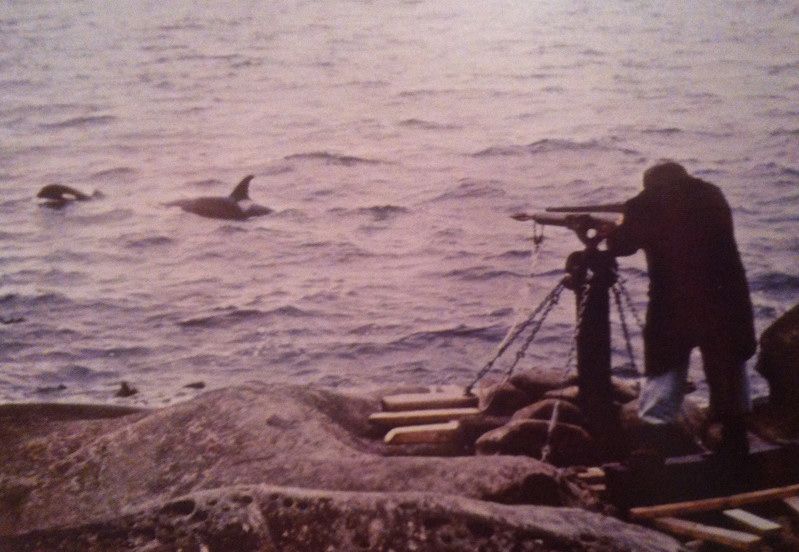

Orcas, or killer whales, were traditionally feared, revered, and respected by the indigenous people of the coast. That sentiment morphed with the growth of commercial salmon fisheries into one of dislike and aggression, as the so-called “blackfish” were seen as dangerous competitors for fish. No one thought it was safe to come near them and it was not uncommon to shoot them. Little was known about their natural history, and they were still scientifically unstudied by the 1960s.

In 1964, the Vancouver Aquarium, which had been in operation for eight years, planned to harvest a killer whale for dissection, study, and use as a model for a realistic statue at the entrance to their facility. A team from the aquarium headed to Saturna, the southernmost of the Gulf Islands, and set up a harpoon on the rocks of East Point, now part of the National Park Reserve.

In due course, a pod of orcas arrived, and the five-metre-long Moby Doll was harpooned. Unexpectedly, it failed to die, as two other members of the pod swam to support it at the ocean’s surface. The aquarium team realized that they could bring the relatively calm animal back alive, and towed it 65 kilometres back to Vancouver.

They called it Moby Doll, mistaking the young male for a female, and exhibited him in a pen in the harbour, where he created a sensation. The public and media flocked to visit.

This was the first ever captive orca and as described by the Saturna symposium organizers, it “triggered a goldrush” on young orcas. Dozens were subsequently captured and put on display in aquariums around the world. The intelligent animals were often taught tricks, and would perform in shows.

Moby Doll survived just 88 days in captivity, but that was long enough to demonstrate the profit potential of live killer whale displays. More here, from the Whale Of A Business site over at PBS.

A few weeks back, I posted a video of Morgan that was created by Loro Parque, along with some quick analysis.

Here’s the video again:

One element of the video that caught people’s attention was the apparent use of a whistle to bridge Morgan, which bears on the question of Morgan’s alleged deafness.

Bridgette Pirtle, a former trainer at SeaWorld Texas, got in touch with her view of the video, and graciously allowed me to share it here:

[UPDATED] A few observations… LoroParque chose some interesting footage to use to show how “well” Morgan is doing. Particularly towards the end, that video appears to give stronger evidence for how she is not acclimating well. The white water looks like displacement not play. Those wide eyes in the closing frames are consistent with behaviors seen in whales anticipating more acts of dominance directed towards her, not of one settling into the hierarchy. Her eyes are of a whale tight and uncomfortable in her social environment. I understand Morgan has a unique history along with some physical disabilities that further distance her from a “regular” orca, but those behaviors are far from that of the ” happy-go-lucky” captive norm. That’s a little more like throwing a Mizzou fan in the middle of KU country. That Tiger is blending in anonymously, hoping to make it through without any altercation. All the while, that Tiger is always watching his tail. The behaviors observed in this video are more consistent with those of learned helplessness rather than proof of her successful acclimation within the social environment of LoroParque.

In regards to earlier comments made suggesting a possibility of the trainers continuing to use auditory stimuli amidst claims of Morgan’s loss of hearing, I feel that this isn’t sufficient evidence to support any speculations of the conflicting claims of poor hearing yet continuing to use the bridge whistle. The session with Jose and Morgan at the slideout isn’t a good indicator of the possibility of a whistle being used as a bridge. Audio is edited and a trainer placing a bridge in his or her mouth doesn’t always mean guarenteed bridge. I was always “chewing on my whistle.” In fact, there is a video on YouTube with me and Halyn doing a hand target learn session for campers where I also go into explaining my habit to the group. I feel the more noteworthy points to take home from this video are that actions viewed are not quite lining up with the words being heard. Although the audio is edited over, I can tell you from the years I worked with him, Jose definitely was just as bad as me at “chewing on the whistle.” Most likely that would get chopped up to a trainer’s superstitious bad habit. There had been a video on YouTube with Rafa using his bridge while working Morgan that would better prove they don’t even really believe their own spin on Morgan’s deafness. It actually may have been one of the first installments of LP’s promo porn regarding Morgan. 🙂

Regardless of whether or not there’s a presence of auditory cues or that there is any substance to Morgan’s situation being compared to that of the whale euthanized by a shotgun blast, I feel the footage incorporated into this LoroParque PSA isn’t necessarily in line with the idealistic image they hope to achieve. Killer whale social structures are extremely dynamic and complex. Morgan’s unique variables contribute even more variables and complexities into this already delicate balance. I would think even an untrained eye would be able to identify the social happenings observed here as being anything but an all-in-all acceptance within her new pod.

This is like Kremlinology, from the bad old days. But it’s nice to have some real experts providing the analysis.

A Tilikum “Splash” segment from the video archives of former SeaWorld trainer Jeffrey Ventre.

From the show producer: “Oh boy, where’s he going?”

Nowhere, it turns out. Tilikum has been doing this segment for almost three decades since this was shot. And a lot has happened over that period of time.

Yet another video about Morgan, and her life at Loro Parque.

As former SeaWorld trainer Jeffrey Ventre notes: “it DOES appear (although no audio confirmation) that a trainer is using a whistle to bridge Morgan at about he 54 second mark. This is contrary to claims that she is deaf.”

Loro Parque trainer Claudia Volhardt also mentions that Morgan is being taught how to pee into a cup, so her hormonal cycles can be monitored. That is a key procedure when it comes to trying to breed Morgan, and Morgan offers SeaWorld (which listed Morgan as a SeaWorld asset when it filed the papers for its recent IPO) extremely valuable wild DNA for its captive breeding program.

Finally, Volhardt takes the opportunity to mention the stranded orca that was shot in the head in Norway in April, contrasting its fate to that of Morgan. On the one hand, it is a fair point since Morgan was “rescued” rather than “euthanized.” On the other hand, topping a standard in which stranded orcas are shot in the head is setting the bar pretty low. And I am pretty sure that none of the release plans proposed for Morgan include a rifle.

All in all, a pretty sophisticated PR effort, aimed at making the public feel okay about Morgan being at Loro Parque.

I’ve been laying off posting about every review of Blackfish that comes across my Google alerts.

But I just came across a fascinating review of Disney’s movie “Chimpanzee,” which dives into a deep discussion of how animals are portrayed in feature films and documentaries:

You could say cinema and nature got off on the wrong foot, or paw, right from the start. In 1926, to much excitement, an adventurer named William Douglas Burden brought back two komodo dragons to New York’s Bronx zoo – the first live specimens the western world had ever seen. Most of that excitement had been generated via a movie Burden had made depicting these semi-mythical reptiles in the Indonesian wild, voraciously devouring a wild boar. By comparison, the real, live komodo dragons were something of a disappointment. They just lay about lethargically in their cage, and died a few months later. It later transpired that Burden’s film had been heavily edited and staged to amp up the drama. The dragons hadn’t actually killed the boar; it had been put there by Burden as bait. The slow reality of nature was no match for the drama of the screen, it turned out. The science couldn’t match the fiction. One of the first to learn this lesson was the film-maker Merian C Cooper. He went on to incorporate elements of Burden’s Komodo expedition into a fictional movie: King Kong.

We have come a long way since Burden’s day in many respects, but that tension between rigorous natural history and populist entertainment is still very much at work in the nature genre, especially now that it has migrated on to the big screen in a big way. Where once we flocked to see animals painted as man-eating monsters in the movies, Jaws-style, now we want to get closer to them, physically and spiritually. There could be several explanations. Maybe it’s guilt at our destruction of their habitats, the proliferation of internet-related animal cuteness or because there are parents keen to give their children something more edifying than Iron Man 3. Or maybe it’s just because we’ve got so much better at filming wildlife. Nature films are one place where all the technological advances of film-making really come into their own: high-definition, 3D, surround sound, lightweight cameras.

But while cinema has made all these advances, nature itself hasn’t really got with the program. Unlike characters in Madagascar or The Lion King, real wild animals haven’t learned to take direction any better than Burden’s giant lizards. It can take years of uncomfortable, patient, expensive observation to gather enough footage for a feature-length documentary. And although it was common practice in the past, faking it is very much frowned upon. We like our wildlife cinema authentic, but we also want it exciting and dramatic, and that is still a challenge.

My view, based on the fact that the more we learn about almost any animal, the more we realize that their thinking and social lives are more complex and sophisticated than we assumed, is that we should err on the side of anthropomorphism. But perhaps “anthropomorphism,” is not even the right word anymore. It is a concept that is based on the idea that humans are unique in the animal world, and so to assume nonhuman animals have intelligence, or emotion, is to assume they are like humans. Instead, I think what science is showing us over time is that intelligence and emotions are to greater and lesser degrees universal among animals. And so perhaps we should start thinking of emotion and intelligence in the animal world as qualities which don’t necessarily set us apart from other animals, but connect us to other animals.

One of the elements of Blackfish that strikes audiences is the degree to which the orca brain has an architecture that suggests cognitive abilities we don’t yet comprehend, cognitive abilities which may in certain respects be superior to human cognitive abilities. So maybe one day as we come to better understand orca cognition and the relative quality of human cognition we will find ourselves orcapomorphizing.

I’m happy to say that this article picks up on exactly that, because Blackfish should make you think, for the first time, that the hierarchy of intelligence and cognition might not always have humans at the top:

Another new film in this vein throws the anthropomorphism debate into fresh relief. Blackfish by Gabriela Cowperthwaite deals not with animals in the wild, but in captivity, namely killer whales at the SeaWorld chain of resorts in the southern US. These creatures are essentially coerced into performing entertaining tricks for the benefit of a public audience, but one whale has been linked to the deaths of three people. Free Willy it ain’t.

As the story progresses, ex-trainers express regret over the treatment of whales, and the lies they routinely trotted out about how “happy” the whales were. There is much sinister footage and gruesome description showing just what killer whales can do to humans if they feel like it.

Blackfish makes no attempt to anthropomorphise its whales and it doesn’t need to. Like chimpanzees, they are evidently highly intelligent and social creatures, and they clearly don’t like what SeaWorld is doing to them – which is in effect imprisoning and torturing them until they snap. Where once they roamed the open ocean, they are now confined to tiny pools, mothers are separated from their calves, and they are forced into unnatural, violent behaviour towards themselves and us. If anything, we empathise with the whales more than the humans because they’re treated like animals. Does that mean they haven’t been anthropomorphised enough?

Like the other nature docs, Blackfish is a gripping movie, with drama and characters and emotion, but unlike them, it’s one that reminds us how much of a gap there is between humans and animals, and between movies and reality, which often amounts to the same thing. Thanks to cinema, we’re able to see nature better, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we’re any closer to it.

During filming, one of the ideas we used to joke about a lot with the former SeaWorld orca trainers is the idea that Blackfish is like “Planet Of The Apes,” except the humans are the apes who are incarcerating a being who they don’t really understand or credit with intelligence and emotion. After a few beers, we’d have Tilikum banging the tank walls, protesting “I am not an animal!”

The idea that an orca, say, or a chimpanzee, might have intellectual or emotional capabilities that exceed a human’s obliterates the idea of anthropomorphism. That makes it a revolutionary, and thrilling, idea that can completely change how you think about, and relate to, animals.

Yesterday I posted two videos with contrasting takes on marine mammal captivity.

Today, there is a third to add: “The Real Truth About Marineland,” which acidly spoofs Marineland’s “Truth About Marineland” video. Maybe tomorrow we’ll see “The Real, Real Truth About Marineland”?

Another great example of the marine mammal video wars. Posted without comment (though it definitely gets points for humor).